(All photographs copyrighted by the Estate of Diane Arbus)

Diane Arbus is a photographer that has a very profound impact on me. When I first saw her photograph of the “grenade kid” — it hit me in the chest and has burned itself in my mind ever since. Upon studying more of Diane Arbus’ work — I found her photographs to be very applicable to my interest in shooting street photography of strangers- mostly as a mode of portraiture.

There is a wealth of knowledge on Diane Arbus (several memoirs, books, and even movies have been made on her), and I cannot say I am an expert on her work. However here is some golden knowledge I have found from one her books published by Aperture that I found incredibly insightful that I wanted to share with you.

Diane Arbus Biography

Diane Arbus is a photographer best known for her square-format photographs of marganlized people in society — including transgender people, dwarfs, nudists, circus people. Although she has always expressed love for her subjects, her work has always been controversial and critiqued heavily by art critics and the general public for simply being “the photographer of freaks” and casting her subjects in a negative light.

Arbus studied photography under Berenice Abbott, and Lisette Model, during the period when she started to shoot primarily with her TLR Rolleiflex in the square-format she is now famous for. Most of her photographs are shot head-on, mostly with consent, and often utilizing a flash to create an surreal look.

Arbus was born in 1923, and it shocked the entire photographic community when she committed suicide in 1971 (at the age of 48). It was reported that she did experience many “depressive episodes” during her life.

Although it has been around 40 years since her passing, she has influenced countless photographers (including myself) and there is still much work being published on her life. In 2006, Nicole Kidman played as Diane Arbus in the motion picture “Fur” — a fictional version of her life story. Also recently published (2011) a psychotherapist named William Schultz published a biography on Arbus named: “An Emergency In Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus“.

To learn more about Arbus, check out the very detailed page of her on Wikipedia here.

Lessons from Diane Arbus

1. Go places you have never been

When it comes to street photography, I feel one of the greatest joys is that it allows you to experience life in a novel and different way. Arbus shares some of her thoughts:

“My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been. For me there’s spending about just going into someone else’s house. When it comes time to go, if I have to take a bus to somewhere or if I have to grade a cab uptown, it’s like I’ve got a blind date. It’s always seemed something like that to me. And sometimes I have a sinking feeling of, Oh God it’s time and I really don’t want to go. And then, once I’m on my way, something terrific takes over about the sort of queasiness of it and how there’s absolutely no method for control.

I feel that one of the greatest traits that a street photographer has is his or her curiosity. Street photography gives us the wonderful opportunity to have the excuse to go to places we generally don’t go — in order to look for interesting photographs and experiences.

Takeaway point: Explore and take the path off the beaten road. If you always shoot street photography in the same place, venture off elsewhere and go down hidden paths that you haven’t been down before. Realize that there is little you can control in terms of what subjects appear, how your background will look at a given time, and how the weather will be for your shots. Simply let the shots come to you, and embrace them.

2. The camera is a license to enter the lives of others

In street photography, we are often timid to approach random strangers and ask to take photographs of them. After all, it may seem weird for us to simply approach someone we don’t know.

However consider how much weirder it would be to approach a stranger without having a camera and having a reason to talk to them. Having the camera is a license to enter the lives of others, as Arbus explains:

“If I were just curious, it would be very hard to say to someone, “I want to come to your house and have you talk to me and tell me the story of your life.” I mean people are going to say, “You’re crazy.” Plus they’re going to keep mighty guarded. But the camera is a kind of license. A lot of people, they want to be paid that much attention and that’s a reasonable kind of attention to be paid.

Arbus also continues by sharing the idea that many people are quite humbled by being paid a ton of attention by having you want to take their photograph.

Takeaway point:

Don’t be embarrassed by your camera and try to hide it when shooting on the streets. Embrace it, and use it as a tool to help you get a license to enter the lives of others. If you see someone on the street that you find interesting and want to get to know more about them — approach them and start chatting with them and explain that you are a photographer and you would like to take their portrait for a project you are working on. Most people become quite humbled by this, and are generally excited to be part of the project.

If you want to take a photograph more candidly, go and take the photograph without permission and then afterwards — explain why you took the photograph. Tell them what project it is for, and what unique part of them that you found that you wanted to capture. When you explain why you think that people are interesting and why you wanted to take a photograph of them, people are generally humbled by that.

3. Realize you can never truly understand the world from your subjects eyes

As a photographer, it is easy to see things from our own perspective. However it is difficult to see the world from your subjects perspective (if not impossible). Arbus explains that although we can try to give our best intents in getting to know our subjects well- our photographs will not always show what we intended. You might have a certain intent when photographing, but the result can be totally different. Not only that, but what we may perceive as a “tragedy” may not be considered as a tragedy to your subject:

“Everybody has that thing where they need to look one way but they come out looking another way and that’s what people observe. You see someone on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw. It’s just extraordinary that we should have been given these peculiarities. And not, content with what we were given, we create a whole other set.

Our whole guise is like giving a sign to the world to think of us in a certain way but there’s a point between what you want people to know about you and what you can’t help people knowing about you.

And that has to do with what I’ve always called the gap between intention and effect. I mean if you scrutinize reality closely enough, if in some way you really, really get to it, it becomes fantastic. You know it really is totally fantastic that we look like this and you sometimes see that very clearly in a photograph. Something is ironic in the world and it has to do with the fact that what you intend never comes out like you intended it.

What I’m trying to describe is that it’s impossible to get out of your skin into somebody else’s. And that’s what all this is a little bit about. That somebody else’s tragedy is not the same as your own“.

Arbus took a lot of photographs of marginalized individuals in society (transgender, dwarfs, circus people, etc) and of course she had her natural prejudices when she took photographs (as well all do). Her individuals would try to present themselves to the world in a certain way, but other people might perceive them in a different way.

For example, if someone dressed up as a rockstar with chains and spiked studs, they may feel that they are giving off the image that they are powerful and cool. However an outsider might see this as frightening, and something abhorrent.

Takeaway point:

Realize that it is impossible to truly get into the mind of someone else. When you are photographing someone in the streets, there is no way to know their entire life history or their character. Sure you might perceive them to be a certain way on the outside, but appearances can be deceiving.

Someone dressed extravagantly (wearing designer labels like Louie Vuitton and Chanel) may look rich on the outside, but can actually be loaded with thousands of dollars of debt. Someone with tattoos all over their face may come off as scary and unapproachable, but they actually may be the nicest person around.

Therefore know your own prejudices and what they are when you photograph. Realize that no photograph is truly objective, and that your photographs are more of a reflection of yourself than the subject. However if you wish, strive to get to know more about your subjects. If you take a photograph of someone candidly and without their permission, perhaps approach them afterwards and chat with them and get to know their personal or life story.

I am currently working on a project titled: “Suits” – my critique on the corporate world and I see the suit as a symbol of oppression. Of course this is my biased view of suits (a lot of people really like wearing suits). Therefore although I am selectively trying to capture photographs of suits looking miserable, I have taken lots of photos of suits looking proud. Sometimes I ask for permission – other times I do it more candidly. However at the end I still try to chat with them about what they do for a living, how they enjoy their work, in order to better understand their stories (compared to my outsider observations).

3. Create specific photographs

When we are shooting street photography, we tend to wander and take photos of anything that interest us. However my personal view (and that of Diane Arbus) is that being very specific when you are out shooting is important- to make a stronger message in your photographs:

“A photograph has to be specific. I remember a long time ago when I first began to photograph I thought, There are an awful lot of people in the world and it’s going to be terribly hard to photograph all of them, so if I photograph some kind of generalized human being, everybody’ll recognize it. It’ll be like what they used to call the common man or something.

It was my teacher Lisette Model, who finally made it clear to me that the more specific you are, the more general it’ll be. You really have to face that thing. And there are certain evasions, certain nicenesses that I think you have to get out of.

On the streets there are so many things to photograph. But we have to be selective. There has to be a reason why we decide to take a photograph of let’s say a little kid skipping in a puddle versus taking a photograph of an old person sitting in a wheelchair.

General photographs tend to be quite boring. If you are more specific in your approach in terms of either your subject matter or approach, not only will your photographs have a stronger collective strength – but they will have more power and meaning to the viewer.

However Arbus shares a problem of trying to be very specific when we are photographing — namely that it can be quite harsh:

The process itself has a kind of exactitude, a kind of scrutiny that we’re not normally subject to. I mean that we don’t subject each other to. We’re nicer to each other than the intervention of the camera is going to make us. It’s a little bit cold, a little bit harsh.

Now, I don’t mean to say that all photographs have to be mean. Sometimes they show something really nicer in fact than what you felt, or oddly different. But in a way this scrutiny has to do with not evading facts, not evading what it really looks like.

When you are specific when you are photographing, you are putting emphasis or a level of exactitude of certain parts of your subjects. For example, you might highlight the glasses on their face, their weathered hands, or the fact that they might be in a wheelchair. This is what you choose to show (or not to show) by framing your camera in a certain way, or even using a certain depth-of-field.

Takeaway point:

Realize that as street photographers, we aren’t always going to show our subjects in the most flattering light. After all, life isn’t always flattering. As Arbus explains, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you h”have to be mean” — but follow your gut and your heart. Strive what feels authentic to you.

4. Adore your subjects

When you take photographs, select your subjects based on what interests you. In Arbus’ example – she was drawn to “freaks” (I’m certain that the term was more politically correct 40 years ago). She explains that she adored them, and found them compelling:

“Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot. It was one of the first things I photographed and it had a terrific kind of excitement for me. I just used to adore them. I still adore some of them, I don’t quite mean they’re my best friends but they made me feel a mixture of shame and awe.

Theres a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats.”

One of the unique parts of Arbus’ work is that she approached subjects that nobody else was really photographing at the time. However rather than just looking at the “freaks” as despicable members of society – she made them human. She explains not only did they excite her, but she found a sense of honor in them – calling them “aristocrats”. After all, they had to deal with much more difficulties in life that us “regular people” often don’t have to. She saw them in a different way than the average person – as venerable.

Takeaway point

Everyone is drawn to a certain type of subject. You might be interested in photos of couples, photos of people jubilant, depressed, photos of children, the elderly, and so on.

I feel it is important to be compassionate to the subjects that you photograph. However once again, we all have our natural prejudices when we photograph – and our photos may not always be so compassionate.

If you also approach a certain subject matter and you want to be unique – don’t just see it how the rest of society sees it. For example children are generally seen as adorable and cute things. Why not try to do the opposite and show them as creatures that can be menacing? Elderly people are generally seen as old and grumpy. Why not take photographs that make them look gentle and compassionate?

Make sure whatever or whoever you photograph that you are passionate about it. Treat your subjects with respect, and know the power of distortion that your lens can have.

5. Gain inspiration from reading

I have written about this in the past, how in order to be more creative with our photography it is important to consume inspiration from places outside of photography. Arbus shares that where she gained some of her inspiration was from reading:

“Another thing I’ve worked from is reading it happens very obliquely. I don’t mean I read something and rush out and make a picture of it. And I hate that business of illustrating poems.

But here’s an example of something I’ve never photographed that’s like a photograph to me. There’s a Kafka story called “Investigations of a Dog” which I read a long, long time ago and I’ve read it since a number of times. It’s a terrific story written by the dog and ts the real dog life of a dog.

Actually, one of the first pictures I ever took must have been related to that story because it was a dog. This was about twenty years ago and I was living in the summer on Martha’s vineyard. There was a dog that came at twilight every day. A big dog kind of a mutt. He had sort of a Weimaraner eyes, grey eyes. I just remember it was very haunting. He would come and just stare at me in what seemed a very mythic way. I mean a dog, not barking, not licking, just looking right through you. I don’t think he liked me. I did take a picture of him but it wast very good.

I don’t particularly like dogs. Well, I love stray dogs, dogs who don’t like people. And that’s the kind fo dog picture I would take if I ever took a dog picture.”

Arbus shares this example that from reading a book by Kafka of a dog- she was able to see something in real life that sparked her imagination. Although she didn’t take a great photograph, it was still a great example of how she was able to gain outside inspiration and apply it to her photography

Takeaway point

Creativity and gaining insights into your photography often come from outside sources. Don’t just consume images from street photography, but diversify. Look at paintings, sculpture, read books, and listen to music. You can never know when one of these outside pieces of inspiration can give your photography a boost of creativity.

6. Utilize textures to add meaning to your photographs

As photographers we can often get obsessed with “the look” of our photographs. We experiment with different focal lengths, shooting at different apertures, using a flash or natural light, color vs black and white, formats, and so forth. However rather than just experimenting for the aesthetic quality, Arbus feels that using different techniques should be for adding meaning.

Arbus shares her experiences in trying to create textures in her image to convey more meaning, rather than just being textured for the sake of being textured:

“In the beginning of photographing I used to make very grainy things. I’d be fascinated by what the grain did because it would make a kind of tapestry of all these little dots and everything would be translated into this medium of dots. Skin would be the same as water would be the same as sky and you were dealing mostly in dark and light, not so much in flesh and blood.

But when I’d been working for a while with all these dots, I suddenly wanted terribly to get through there. I wanted to see the real differences between things.

I’m not talking about textures. I really hate that, the idea that a picture can be interesting simply because it shows texture. I mean that just kills me I don’t see whats interesting about texture. It really bores the hell out of me.

But I wanted to show the difference between flesh and material, the densities of different kinds of things air and water and shiny. So I gradually had to learn different techniques to make it come clear. I began to get terribly hyped on clarity.”

For Arbus’ earlier work she started with a Nikon 35mm camera, but in order to better achieve her creative vision she switched to a TLR Rolleiflex – in which she worked the square format and achieved extra detail in switching from small to medium-format.

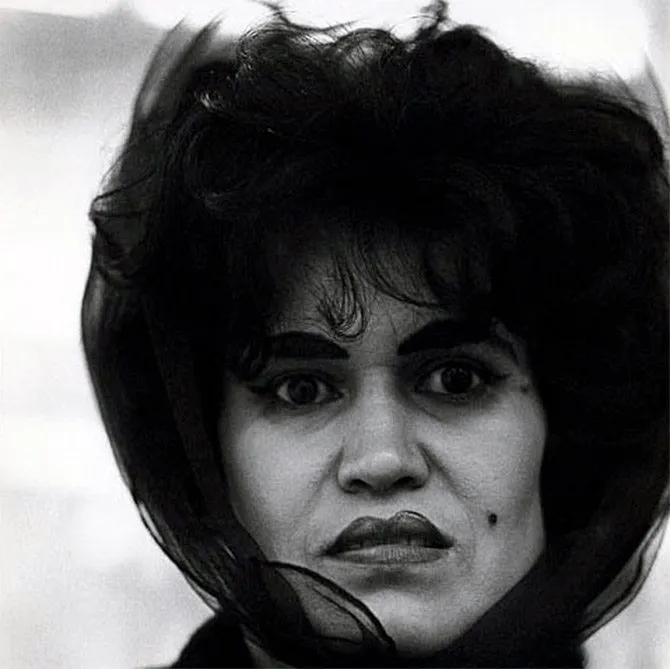

Arbus also worked quite a bit with flash, which brought out more textures and light in her photographs. Many of her photographs taken during the day (such as the photograph of the woman with the veil above) show that she balanced the fill flash and the background light – creating a quite surreal effect. Not only that, but it better brought out the texture in the woman’s face, the fabric of the veil, and of her light-colored hair and fur coat.

Takeaway point

When you decide to use a certain camera, focal length, flash vs natural light, black and white versus color, etc — think about the added meaning you want to give to your photographs. For example, if you use a 28mm lens (rather than a 50mm lens) consider why you are trying to do that. Instead of just making more distortion for the sake of it — perhaps you should use it to create a more sense of immediacy and intimacy with your subject. When shooting in black and white – are you trying to document something sad and depressing or want to focus on forms and shapes? If working in color- what about the color adds meaning to your photographs?

Experiment freely with your photography, but don’t get carried away for trying something new for the sake of trying something new and trying to be different. Think about the meaning you will add to your images.

7. Take bad photos

As photographers, we all hit plateaus or feel lack of inspiration at times. How do we get over this? Arbus suggests the idea of purposefully trying to “take bad photos”:

“Some pictures are tentative forays without your even knowing it. They become methods. It’s important to take bad pictures. It’s the bad ones that have to do with what you’ve never done before. They can make you recognize something you had seen in a way that will make you recognize it when you see it again.

By forcing ourselves to take bad photographs, it will cause us to understand what makes a good photograph. Also when looking at our bad photographs, we can learn how to improve on our pre-existing photography.

Arbus also discounts the importance of composition in her photography:

“I hate the idea of composition. I don’t know what good composition is. I mean I guess I must know something about it from doing it a lot and feeling my way into and into what I like. Sometimes for me composition has to do with a certain brightness or a certain coming to restness and other times it has to do with funny mistakes. Theres a kind of rightness and wrongness and sometimes I like rightness and sometimes I like wrongness. Composition is like that.”

Looking at Arbus’ photographs, I would say that they are well-composed. She fits her subjects well in the frame, and positions them which give the images a sense of balance and harmony.

However she also mentions an important point that sometimes good compositions come from funny mistakes. Good compositions (although they should be intentional) can sometimes be unintentional.

Takeaway point

Composition is very important in street photography – as it helps the viewer understand who the subject in your photograph is. Not only that, but there is a natural sense of balance and beauty in composing something well.

There are lots of photographs you are going to take that are bad. They are either going to be boring or poorly composed.

However learn from your mistakes, and realize that making mistakes is part of the creative process. Without making bad photographs, how would we know what are our good photographs?

8. Sometimes your best photos aren’t immediately apparent (to you)

I believe that photographers (myself included) are awful editors of their own work. We often get emotionally attached to our images, and can often take our bad photographs as good photographs. On a similar vein, we can also overlook our best photographs and not realize that they are interesting. Arbus explains this more in-depth:

“Recently I did a picture—I’ve had this experience before—and I made rough prints of a number of them, there was something wrong in all of them. I felt I’d sort of missed it and I figured id go back. But there was one that was just totally peculiar. It was a terrible dodo of a picture. It looks to me a little as if the lady’s husband took it. Its terribly head-on and sort of ugly and there’s something terrific about it. I’ve gotten to like it better and better and now I’m secretly sort of nutty about it.”

First impressions aren’t always everything. When we first look at our photographs, we may not see anything interesting. However once we sit on them- and think about them some more, they can become more interesting over time.

Takeaway point

I feel it is always important to get a second-opinion on your photographs. If you took a photograph that you think is interesting – your own judgement may not always be the best. Ask people you trust and respect for their feedback both online and offline. Ask them both what they like and what they dislike about the photograph, as they are less attached to the photograph than you and can give you more honest feedback.

9. Don’t arrange others, arrange yourself

One of the great appeals of street photography is that there is little we can arrange. Arbus shares that when she photographs people, she prefers to arrange herself instead of her subjects:

“I work from awkwardness. By that I mean I don’t like to arrange things if I stand in front of something, instead of arranging it, I arrange myself”.

I like to take lots of candid photos, but I also like to take photos when I arrange my subjects in a certain way I’d like to capture them. However it is true that the most interesting photos I have taken are generally the ones that aren’t posed.

Takeaway point

If you want to make an interesting photograph of someone but you don’t want to arrange them in a certain way or ask them to pose for you – arrange yourself in a different way. Take a photo of your subject form different angles – form the left, head-on, and from the right. Crouch, or stand up. Change your positioning which will help give the scene a better sense of clarity.

10. Get over the fear of photographing by getting to know your subjects

Getting over your fear of shooting street photography is one of the biggest challenges all of us face. If you decide to photograph a certain location over and over again, it may be a good idea to get to know the community and your subjects to overcome that fear. Arbus shares her experiences shooting outsiders at a park:

“I remember one summer I worked a ltot in Washington Square Park. It must have been around 1966. The park was divided. It has these walks, sort of like a sunburst, and there were these territotries stalked out. There were young hippie junkies down one row. There were lesbians down another, really tough amazingly hard-core lesbians and in the middle were winos. They were like the first echelon and the girls who came from the Bronx to become hippies would have to sleep with the winos to get to sit on the other part with the junkie hippies.

It was really remarkable. And I found it very scary. I mean I could become a nudist, I could become a million things. But I could never become that, whatever all those people were. There were days I just couldn’t work there and then there were days I could.

And then, having done it a little, I could do it more. I got to know a few of them I hung around a lot. They were a lot like sculptures in a funny way. I was very keen to get close to them, so I had to ask to photograph them. You cant get that close to somebody and not say a word, although I have done that.”

Diane Arbus often describes herself as being quite awkward and shy when photographing. She had her doubts, fears, and concerns when photographing. The interesting thing to note is that most of her photos are very upfront and close to her subjects.

Therefore to overcome her fear of shooting these people in the park (who frightened her) – she would revisit over and over again, and found out over time she became less timid. Not only that but she got to know the people there, and asked for permission. This helped her feel more comfortable and photograph the people in the area.

Takeaway point

We all have a certain degree of fear when it comes to shooting street photography. Know that everyone has it.

There are many ways to get over the fear of shooting street photography (download a copy of my free e-book on overcoming your fear of shooting street photography here). However know that naturally the more you shoot street photography the more up-front and honest you are about it, you will become more comfortable over time. I can speak from experience that I am definitely more comfortable shooting street photography now than I was around two years ago.

Don’t also be ashamed to ask for permission. If you feel uncomfortable and want to take a photograph, just ask for permission. The worst that will happen is that they will say no, and you simply move on. The best thing that can happen is that they will say yes- and you will build that connection.

11. Your subjects are more important than the pictures

Although Arbus was criticized much during her lifetime (and even now today) for being uncompassionate – she certainly did care for her subjects more than the photos themselves:

“For me the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture. And more complicated. I do have a feeling for the print but I don’t have a holy feeling for it. I really think what it is, is what its about. I mean it has to be of something. And what its of is always more remarkable than what it is.”

Arbus explains how for her the subject of the photograph is more important (and often more interesting) than the photograph itself. She explains that the photos can be interesting, but she doesn’t get that same “holy feeling” she gets with her subjects.

Takeaway point

As street photographers we strive to take interesting photos. But remember to not let that overshadow the importance of your experiences and connections with your subjects.

Know that human beings are both more interesting and important than just images of them. Photos are two-dimensional while people are three-dimensional to them. Photos are mute while people can speak about their experiences.

Conclusion

Diane Arbus was not only an incredible photographer, but she also had deep feelings and emotions with her subjects – which I feel come across in her photography. She truly followed her heart in her photography, and took photos of subjects that both interested her – and that she felt compassion and warmth to.

As street photographers we can relate much with the types of photos that Arbus took (as many of them were on the street). Although we can learn much from the images that she shot, we can learn more from her personal philosophy around why she took the photos the way she did- and even her approach.

Don’t be shy to ask for permission, and get close and intimate with your subjects. You may have natural fears approaching people (as all of us do) – but photograph openly, honestly, and from the heart. People may criticize you for what you do, but as long as you follow your own moral compass- ignore what others have to say.

To see the entire introduction to the Aperture Monograph of Arbus’ life, click here.

Books by Diane Arbus

If you want to learn more about Arbus, below are some photo-books (and biographies on her) that I recommend you to purchase:

Diane Arbus: Aperture Monograph

A great introduction to Arbus’ work – and this is also the book that I used to construct this article. Always recommend any publications from Aperture!

Diane Arbus Revelations

This book was published after her show at the SF MOMA, which is a very thorough history of her work, a chronology, and insights about her work. The book is beautifully published, and also an incredibly comprehensive resource of her most memorable images.

Diane Arbus: A Biography

A biography published on Arbus by Patricia Bosworth which is understood to be one of the best published that gives you a through insight into the life and work of Arbus.

An Emergency in Slow Motion: The Inner Life of Diane Arbus

One of the most recent books to be published on Arbus (2011) by psycho therapist William Todd Schultz. Although it has received mixed reviews, I think it fascinating to hear Schultz’s views on Arbus’ very difficult life- with some of his thoughts based on his experiences working as a psycho therapists. For the hardcore Arbus fans.

How does Arbus’ work make you feel and how has it influenced you and your photography? Share your thoughts in the comments below!