I recently got a new book in the mail: “Dorothea Lange: Aperture Masters of Photography” (courtesy of Aperture) and was deeply inspired and moved by her work, life, and philosophy.

I have always known Dorothea Lange’s work documenting the Great Depression (and her famous “Migrant Mother” photograph), but didn’t know much about her life and philosophy. In this article I will share some of the lessons that Dorothea Lange has taught me about photography, and how you can apply that philosophy to your own work:

Dorothea Lange’s history

Dorothea Lange was born on May 26, 1898 in New Jersey, and traumatically contracted polio at 7 years old, which left her with a weak right leg and permanent limp. Regardless of this disability, she was able to pursue her photography with full zest. This is what she says of her disability:

“It formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me and humiliated me. I’ve never gotten over it, and I am aware of the force and power of it.”

Lange ended up studying photography at Columbia University in New York City, and after her studies moved to San Francisco, where she opened up a successful portrait studio. For the majority of her life, she lived in Berkeley. In 1920 she married the painter Maynard Dixon and had two sons with him.

On the onset of the Great Depression, she started to photograph more photographs on the street, and less in the studio. Her emotional and raw photographs of unemployed and homeless people caught the attention of local photographers, which lead her to getting a job with the federal Resettlement Administration (RA), later called the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

In 1935, Lange divorced Dixon and married economist Paul Schuster Taylor, Professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley. This gave her the economic freedom to pursue her photography full-time. This ended up being a beautiful partnership, as Taylor was able to educate Lange in social and political matters. Together, they were able to document poverty and the exploitation of sharecroppers and migrant laborers for 5 years. Taylor’s job was interviewing the workers (he was fluent in Spanish), and also gathering economic data. Dorothea Lange focused on documenting the conditions with her camera.

Lange’s work from 1935 to 1939 brought a lot of attention of the horrible living conditions of the sharecroppers, displaced farm families, and migrant workers to the public attention. Many of her images have become iconic of the Great Depression.

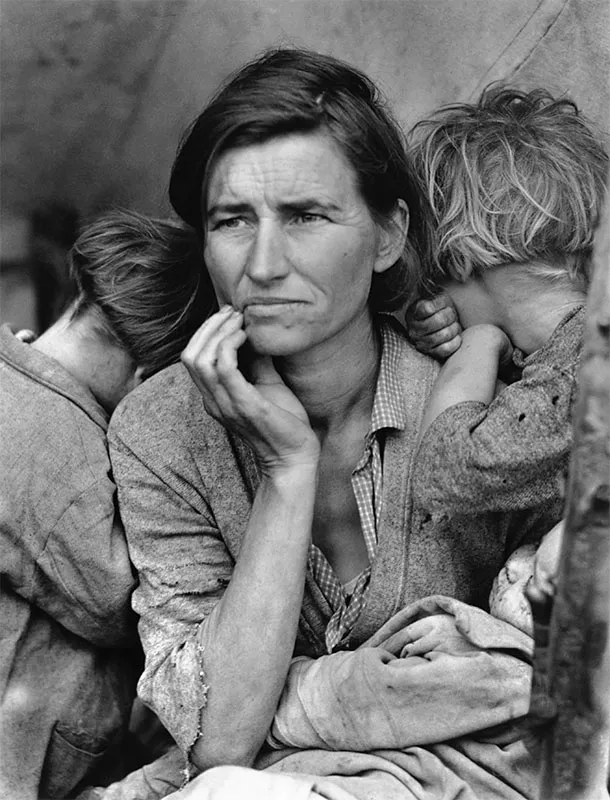

Lange’s most famous photograph is titled “Migrant Mother.” The woman in the photo is Florence Owens Thompson, and Lange explained the experience of shooting that photograph in 1960:

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

Once Lange returned home, she gave the photographs to an editor of a San Francisco newspaper about conditions of the camp. The editor then told the federal authorities whom urged the government to rush aid to the camp to prevent starvation.

In 1941, Dorothea Lange was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for excellence in photography. However after Pearl Harbor (when Japanese-American citizens were forced into internment camps), she gave up the award and dedicated her efforts to documenting the injustice of the Japanese-American internment.

Her images were very critical of the American government — so much that the Army impounded the majority of the images. Most of them haven’t been seen for the last 50 years. You can now see the images in the newly published book: “Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment”.

In 1945, Lange was invited by Ansel Adams to accept a position at the fine art photography department at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA). Later in 1952, Lange co-founded Aperture magazine. Lange continued to photograph and worked on her one-woman show at the NY MOMA for a retrospective of her work. Unfortunately she died before the show was exhibited. She passed away on October 11, 1965 in San Francisco, California at age 70.

To learn more about Dorothea Lange’s work, I recommend watching the film: “Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning”:

Lessons Dorothea Lange Has Taught Me About Street Photography

Even though Dorothea Lange was a documentary photographer (not a street photographer), I feel many of the precepts are the same. She had a deep love of humanity, people, and wanted her photographs to make a difference in society. Here are some lessons she has taught me:

1. Learn how to see

A lot of times we are obsessed with cameras, gear, lenses, and other things to help us become better photographers. We learn endlessly about technique, approaches, and technical settings to improve our image making.

But what is the best way to become a better photographer? Learn to become better at seeing.

This is what Dorothea Lange had to say about the importance of seeing in photography:

“Seeing is more than a physiological phenomenon… We see not only with our eyes but with all that we are and all that our culture is. The artist is a professional see-er.”

Seeing in photography isn’t just seeing what might make a good photograph. Rather, you see with all of your ideology and perceptions of the world. We see the cultural context of scenes we want to photograph. But as a photographer, we are able to “see” deeper into reality than others.

What is the benefit of seeing, and how can we become better at seeing? Lange gives us some advice in terms of not rushing things, taking our time, and meditating upon what is before our very eyes:

“This benefit of seeing… can come only if you pause a while, extricate yourself from the maddening mob of quick impressions ceaselessly battering our lives, and look thoughtfully at a quiet image… the viewer must be willing to pause, to look again, to meditate.”

The best images are the ones that are full of information, emotion, and context that challenge the viewer to “…pause, to look again, to meditate.”

How important is the camera in terms of seeing? According to Lange— not very much:

“A camera is a tool for learning how to see without a camera.”

I have personally found that photography has given me the opportunity to be more curious. Now with photography, I look at scenes more intently. I can now “see” things that I didn’t see before. I have also discovered a phenomenon in which I can see more things when I have a camera around my neck or in my hand.

Remember, seeing is a gift. The last words of wisdom Dorothea Lange gives us is this:

“One should really use the camera as though tomorrow you’d be stricken blind.”

Takeaway point:

No amount of camera gear, lenses, or technical know-how will teach us to be more empathetic, loving, and curious “see-er’s.”

The best photographers are the ones who are able to see the world in a unique way. They are able to look at people, scenes, and moments with a different perspective from others.

So as an exercise— try to be more mindful when shooting street photography. Don’t look at things quickly and fleetingly. Look at things deeply. Think about the significance of how something looks like.

Also create open-ended photographs. Don’t have your photographs simply tell the facts. Provide more questions than answers in your photographs, which will cause your viewers to be more engaged (emotionally and intellectually) with your images.

2. Work your theme to exhaustion

“Pick a theme and work it to exhaustion… the subject must be something you truly love or truly hate.” – Dorothea Lange

I think in today’s day and age, we are quickly bored and exhausted. We want to finish things quickly, efficiently, and go onto the next project.

However I think if you want to really create a strong body of work, you should try to work on a long-term photography project, and as Dorothea Lange said, “work it to exhaustion.”

Dorothea Lange also mentioned when working on a project, “…the subject should be something you truly love or truly hate.”

So if you are working on a long-term photography project, make sure it is something you are really passionate about. If it is something you deeply love, you will continue to pursue it like you would continue loving a person. If the project you are pursuing is something you really hate or something that makes you really upset (let’s say the gentrification of a neighborhood, social injustice, or homelessness) you can put your passion to it in a good way.

But how long should we work on a project? How long is “long enough”— and how do we know when we have truly “exhausted the possibilities” of a project? There is no real way to know— but Dorothea Lange says we often stop our projects “too soon”:

“Photographers stop photographing a subject too soon before they have exhausted the possibilities.”

Takeaway point:

When you are working on a photography project, keep pushing forward. When you think you’re done with it— you’re not quite done. Keep working until you can exhaust all the possibilities.

This is the same with camera equipment and gear. Don’t try to upgrade your gear until you think you have truly exhausted all of the possibilities of your medium.

One of the lessons I learned about working on photography projects is when you no longer have passion for a project, that is the moment you need to keep pushing forward. When you keep pushing forward, it forces you to be more creative to approach your project in different ways that you might have not explored yet.

So what are some ways you haven’t exhausted all of your creative possibilities yet? Keep working your themes until exhaustion.

3. Every photograph is a self-portrait

“Every image he sees, every photograph he takes, becomes in a sense a self-portrait. The portrait is made more meaningful by intimacy – an intimacy shared not only by the photographer with his subject but by the audience.” – Dorothea Lange

The photographs we take are less of a reflection of our subjects, and more of a reflection of ourselves.

Dorothea Lange agrees with this mentality by taking it further— the images we also see are self-portraits.

Generally we are interested in photographers or subject matter that resonate with us. That is something that is extremely personal. The photos we are interested in are a reflection of our own self-values, and how we see the world.

For example, if you are drawn to raw and gritty street photography— perhaps you grew up in a raw and gritty environment. Therefore it resonates with you. Or perhaps the opposite— you grew up in a safe and sheltered environment, and therefore your interest in raw and gritty street photography is a reflection of the fact that you despised the safe and sheltered environment in which you grew up.

Personally I grew up in a socio-economically disadvantaged background in which I had to worry about whether my mom could pay the bills at the end of every month. Many of my friends succumbed to joining gangs and drugs. Therefore whenever I see people on the streets who are tatted up and perhaps gang-affiliated, I think of my friends growing up.

Even though I am a happy and smiley guy on the outside, I feel that there are parts of me that are deeply cynical inside. Therefore for my street photography, I think my work is very dark, grim, and a little bit on the pessimistic side. My photos reflect of my inner being and soul.

Takeaway point:

So how are your street photos a reflection of yourself? What kind of subject matter are you drawn to? How do you empathize with your subjects? How do the photos you take reflect your own personal history or background?

Make your street photography personal and a self-portrait of yourself.

4. Live with your camera

“I believe in living with the camera, and not using the camera.” – Dorothea Lange

The worst feeling is when you see a great street photography opportunity, but you accidentally left your camera at home.

I feel that photography has helped me so much in my personal life. When I have a camera with me, I am much more attentive and attuned to my surroundings— in terms of what I am doing, who I am with, and what I am experiencing.

Don’t just think about using a camera and making photos, think about living with the camera— and having your camera become another appendage of your body, as Dorothea Lange explains below:

“… put your camera around your neck along with putting on your shoes, and there it is, an appendage of the body that shares your life with you.” – Dorothea Lange

The camera isn’t just a tool or a device that captures images. It is an extension of your body. It is an extension of your eye. It is another appendage, like an extra arm or a limb. The camera is a loyal partner that shares your life experiences with you, and a partner who helps you live life more vividly.

Takeaway point:

What are some other ways you cannot just use the camera, but live with the camera?

One of my suggestions is to always have your camera sitting next to you. If you are sitting at work, just keep your camera on your desk right next to your computer. If you are driving, keep your camera in the passenger seat. If you’re going for a walk, keep your camera around your neck or in your hand.

I think the one device we have the closest physical and intimate relationship with is our smartphone. If you find yourself having a tough time always carrying your camera with you on a daily basis, perhaps you should make your smartphone your primary shooting device. With programs such as VSCO, you can truly make great photos regardless of the camera you use.

So how are some other ways you can spend more time with your camera, and make your camera your partner for life?

5. Dorothea Lange’s working approach

How did Dorothea Lange make such riveting, emotional, and timeless images? She talks about her working approach below:

“My own approach is based upon three considerations: First – hands off! Whenever I photograph I do not molest or tamper with or arrange. Second – a sense of place. I try to picture as part of its surroundings, as having roots. Third – a sense of time. Whatever I photograph, I try to show as having its position in the past or in the present.”

I don’t think we necessarily have to shoot how Dorothea Lange does, but thinking about her working method does give us some insight on how we can become better street photographers:

First: “Hands off”

Dorothea Lange was a purist in the documentary sense— she didn’t like tampering or influencing the scene. She didn’t like pre-arranged or setup photographs.

However at the same time, she would take portraits of her subjects with their consent and permission.

I think the way we can interpret this in street photography is to try to capture what you see before you as “authentically” as you can. We all have different interpretations of reality, and there is no true objective “reality” of what we experience or see.

But stick to your heart, and photograph what feels authentic to you.

Second: A sense of place

When you’re making street photographs, try to also include a “sense of place” — meaning, putting your subject in the context of a background or environment.

So when you’re taking photos of people on the streets, try to incorporate the background as much as your subject. If you’re shooting a street in New York City, what part of the scene screams “New York City?” How does the environment influence your subject, and vice-versa?

A tip to get better photos with a good sense of place is to take a step back. I do believe that “if your photos aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough”— but there are times where taking a step back and getting a “sense of place” will make a stronger image.

Third: A sense of time

What about the street photographs you take show a “sense of time?” Is it the clothing of people? Is if the environment? Is it the devices they are holding?

If you want to truly make timeless street photos— perhaps photograph in areas that you know are rapidly changing and developing. If you live in an area that has construction, go there and photograph. It will look dramatically different in a year, two, five, or ten years from now.

But also realize that any street photograph you take is technically history. Sometimes we romanticize the past. We look at street photos taken in the 1920’s by Henri Cartier-Bresson and we daydream about the people who used to walk the streets with top hats. But back then, it was normal to wear top hats in public.

Perhaps 20 years from now, it will look really strange to see “old” photos of people on their iPhones. So perhaps that is a phenomenon we can document right now. It isn’t too late to make history, and to show a sense of time.

6. Don’t shoot preconceptions

“To know ahead of time what you’re looking for means you’re then only photographing your own preconceptions, which is very limiting, and often false.” – Dorothea Lange

One of the most difficult things to do when you’re out shooting street photography (or traveling) is not to be prejudiced and to shoot your pre-conceptions.

For example, let’s say you go to Paris. You might have seen tons of photographs of old couples kissing at cafes, and you might try to shoot those clichés.

Or let’s say you have seen lots of photographs of homeless people. You might go out and just try to shoot photos of homeless people looking sad and depressed.

One of the things I learned from studying sociology and doing “field research” is to go into any scene with an open mind. Rather than having a pre-conceived notion before you go out and shoot, go with an open mind and photograph what you see and experience.

So when it comes to traveling, I try not to do too much research before going to a certain place. Rather, once I arrive in a certain place, I ask the locals and people I meet about the place. They then tell and teach me about the culture, customs, and history of the place. I feel this gives me a much more open-mind about the environment which I visit.

And also when you’re working on a street photography project, don’t always try to force things into your project. For example, let’s say you are trying to do a project of homelessness. You might go in with a pre-conceived notion that everyone who is homeless is depressed and sad. But the reality of the matter might be that not everyone who is homeless is unhappy. So by having pre-conceived notions, you close off your mind to other opportunities and realities.

Dorothea Lange gives us further instructions when going to photograph— to be “as ignorant as possible”:

“The best way to go into an unknown territory is to go in ignorant, ignorant as possible, with your mind wide open, as wide open as possible and not having to meet anyone else’s requirement but my own.”

Takeaway point:

We often look down on ignorance. We think that being ignorant is a disease, and that people who are “smart” aren’t ignorant.

But sometimes being selectively ignorant can be a strength. Children are ignorant, and therefore their minds are open to endless possibilities. When we fill out heads with too much preconceived ideas, we close off our opportunities to imagination, ingenuity, and creativity.

So if you were to start off street photography all over again, what are some pre-conceived notions you would kill to help you become like a child again? To help you be more happy, fun, and curious when it comes to street photography?

Conclusion

The work of Dorothea Lange is hugely inspirational— in terms of how she lived her life, how she documented her subjects with great sincerity and emotion, and how she photographed social injustice and used her photography to raise political awareness.

So how can you learn how to see more conscientiously on the streets? How can you learn to be more tenacious and “work your themes to exhaustion”? How can we learn to apply our photography to become more of a self-portrait of ourselves? How can we spend more time “living” with our cameras, and making it an extension of ourselves? How can we better show “authenticity”, a sense of place, and a sense of time with our photos? How can we be more open-minded with our street photography?

There are all questions we can ponder— and learn how to become more loving, empathetic, and conscientious street photographers.

Learn more about Dorothea Lange

If you want to learn more about the work of Dorothea Lange, I highly recommend picking up a copy of “Dorothea Lange: Aperture Masters of Photography” to get an overview of her most famous images and commentary that will help you think deeper about her work.

To learn more about Dorothea Lange’s work, I recommend watching the film: “Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning”:

Learn from the masters of street photography

- Alec Soth

- Alex Webb

- Anders Petersen

- Andre Kertesz

- Bruce Davidson

- Bruce Gilden

- Daido Moriyama

- David Alan Harvey

- David Hurn

- Diane Arbus

- Elliott Erwitt

- Eugene Atget

- Eugene Smith

- Garry Winogrand

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

- Harry Callahan

- Jacob Aue Sobol

- Joel Meyerowitz

- Joel Sternfeld

- Josef Koudelka

- Lee Friedlander

- Magnum Contact Sheets

- Magnum Photographers

- Mark Cohen

- Martin Parr

- Mary Ellen Mark

- Robert Frank

- Saul Leiter

- Sebastiao Salgado

- Stephen Shore

- The History of Street Photography

- Tony Ray-Jones

- Trent Parke

- Walker Evans

- Weegee

- William Eggleston

- William Klein

- Zoe Strauss