Josef Koudelka is one of my favorite photographers of all-time. I love how he has been able to craft his life around photographing only what he wanted to photograph, how he is able to capture emotional and empathetic images (especially in his “Gypsies” project), his ability to continue to re-invent his photography (switching from 35mm to panoramic), and his absolute dedication to his craft.

I recently came across a superb interview with Koudelka titled: “We Are All the Same”: A Conversation with Josef Koudelka” via my friend Karl Edwards from StreetShootr.com.

I will share some personal lessons that Koudelka has taught me about photography and life below. If you want to learn more about Koudelka, I recommend you to read my article on him: 10 Lessons Josef Koudelka Has Taught Me About Street Photography.

1. Create the conditions of your life

Koudelka is famous for being the ultimate nomad in terms of photography. He has been traveling the past 45 years, mostly homeless— and has pursued only photography projects which interest him.

There are lots of stories of him sleeping on the floor of the Gypsies (when he was photographing them, they actually felt bad for him), crashing at the offices of Magnum, and him borrowing equipment, film, and darkrooms from friends and colleagues.

He has lived his entire life on a shoestring budget— and has the ultimate freedom: freedom of time, and the freedom to photograph exactly what he wants (how he wants).

Many of us don’t have this luxury— to just quit our lives and become nomadic, traveling photographers.

However Koudelka has made the conscious decision to dedicate his life to travel and photography— at the expense of having a steady family life, having a home, and a stable income.

In the excerpt below, he shares some of his personal philosophy when it comes to this:

Laura Hubber: You’re famous for not taking assignments. How do you choose your subjects?

Koudelka: I know what I want to do and I do it. And I’ve created conditions so I can do it—I’ve been doing it for 45 years. People who do assignments are being paid and they are supposed to do something. I want to keep the freedom not to do anything, the freedom to change everything.

Takeaway point:

You control your life. You control your destiny. I believe that “reality is negotiable” — there is no excuse for not pursuing what you love.

The only excuse we make is that we have to make sacrifices. Everything we decide to pursue in life has a cost.

So if your dream in life is to travel the world and make photographs for a living— you can do that. But the question is: “What am I willing to sacrifice in my life?” You will probably have to sacrifice a lot: like Koudelka. You probably won’t have a stable income, you won’t have enough money to buy a BMW or expensive cameras, you will have the stress of figuring out how to make ends meet, you won’t have a stable family life, and probably will be seen as a strange outsider by others.

But if you’re willing to make these sacrifices to live out your dream— go for it.

Similarly, I know a lot of people who make excuses that they don’t have time to make photos. But it isn’t that they don’t have time— it is because they are unwilling to sacrifice the time they spend doing other stuff.

For example, if you have a full-time job, you can always make time by leaving your house an hour early, and taking photos on the way to work. You can take your 30minute–1 hour lunch break to make photographs around your office building. If your office building area is boring, go make photos right after you are done work. I know it is tiring and exhausting to make photos after a long and stressful day of work— but if you are truly, insanely passionate about photography— you will make this sacrifice.

Perhaps you can also decide to work a part-time job, or a job with flexible hours, in order to travel and shoot photography. I know some photographers who work on airlines, which gives them the freedom to travel and shoot. I know some friends who teach English in foreign countries, because it gives them the opportunity to live in a foreign country, travel, and also shoot.

Reality is negotiable— just think of how bad you want it.

Related article: Advice for Aspiring Full-Time Photographers

2. Follow your intuition

One of the questions that a lot of photographers ask me is: “How do I know what kind of project to work on?”

Koudelka gives the practical advice of following your intuition:

LH: What’s the main motivation for you to choose a subject?

Koudelka: I’m an intuitive person.

LH: If it speaks to you, you go.

Koudelka: You know, people ask all the time why I photographed gypsies. I’ve never known. I’m not particularly interested to know.

LH: Is it possible that you were drawn to the way Roma are free from the state?

No, not at all [pause]. You know, I didn’t grow up with American cinema like many photographers. I was from a little village. I was never fascinated by the United States. But I remember seeing photographs from the Farm Security Administration and they moved me very much. It wasn’t because of the style of the photography—it was because of the subject. Maybe you’ll find something similar with Gypsies too.

Koudelka doesn’t give a super-compelling reason why he chooses to shoot what he shoots, or why he decided to follow the Roma people and create his “Gypsies” book.

He has rather followed his intuition and his curiosity.

Takeaway point:

I think it is important to follow your nose in street photography. If you are out on the streets, you don’t always need a reason to make a certain photograph.

I have a rule: if I find a scene or a moment that I get a gut-feeling that it might be interesting to shoot, I take the photograph. You want to listen to your gut— and follow your intuition what might be a good shot, rather than letting the editor of your mind say, “No— don’t shoot that, it is a rubbish shot.”

For all the photography projects I have personally worked on, it was generally personal. For example, I started my “Suits” series after I got laid off my corporate job when I was working as a “Suit”. I got so obsessed about money, power, and “trying to keep up with the Joneses” that I became a work-a-colic just to earn more money and prestige. But now when I see people wearing suits, I can empathize with them— and feel sorry for them.

For my “Only in America” series which I am pursuing at the moment, I came to realize that the best photos I take are in my own backyard (or country for this matter). I have done a lot of international travel the last few years, and I am starting to realize that I need to spend more time at home, and photograph my own home and culture. I have been deeply moved and inspired by “The Americans” by Robert Frank, as well as the other American photographers such as William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld, Lee Friedlander — and many others. So through this project, I want to show my own version and viewpoint of “America” — it is a project that my gut and my heart is telling me to do.

So if you are trying to figure out what you want to shoot, go out and shoot with an open mind. Have a blank slate. Don’t go out with too much of a pre-conceived notion. Photograph simply what interests you.

After a few months, start to look at your images more analytically. Start to label and tag your images, and see what kind of subject matter you are drawn to. Are you interested in photographing faces? Are you interested in capturing gestures and moments? Are you interested in urban landscapes?

Once you find what kind of subject matter interests you— follow your curiosity and intuition. Keep shooting it until your heart tells you it is time to stop.

I think our subconscious mind has great power. Give it respect, and listen to your gut.

Related articles: On Shooting For Your “Inner Scorecard” and Advice for Young Street Photographers

3. On composition

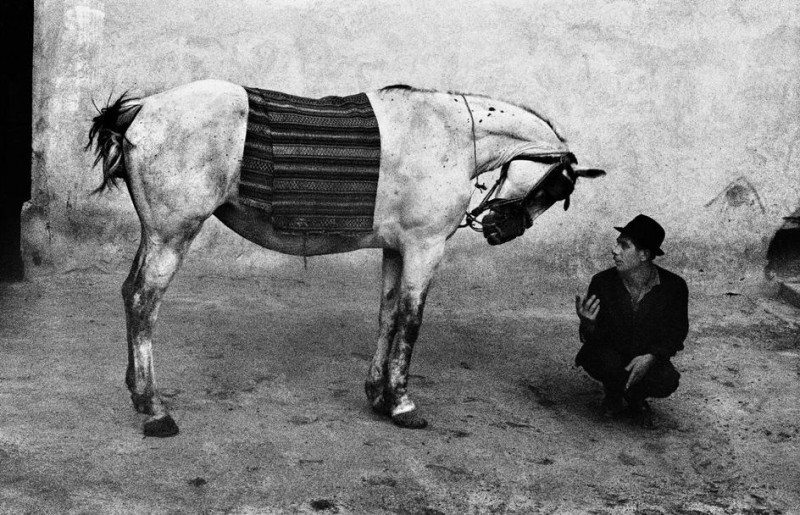

Koudelka has some amazing compositions in his photography. You can see a lot of Triangles compositions(especially in his “Gypsies” book). He also has some great simple “Figure-to-ground” compositions that you can also see in his “Exiles” book.

In the interview, they ask Koudelka his thoughts on composition:

LH: How important is composition in your photographs?

Koudelka: It’s not a good photograph without good composition. Originally I’m an aeronautical engineer. Why do airplanes fly? Because there is balance.

I find it fascinating how Koudelka’s background in engineering has informed his composition. One of the main purposes of composition is to add balance, shape, and form to the images.

Furthermore, when asked what makes a good photograph— Koudelka shares that it is very subjective at times. A photograph speaks to people differently— based on their life experiences or how they interpret the image:

Koudelka: A good photograph speaks to many different people for different reasons. It depends on what people have been through and how they react.

Also another good way to make a strong photograph is to ask yourself, “What am I going to remember?” It is to make a photograph that burns itself in your mind, and in your heart:

Koudelka: The other sign of good photography for me is to ask, “What am I going to remember?” It happens very, very rarely that you see something that you can’t forget, and this is the good photograph.

Takeaway point:

If you want to learn more about composition, I recommend reading my series on composition and street photography (see links below).

Koudelka is one of the best photographers because he is able to marry both composition and content. His photographs are beautifully composed, but also have a deep sense of soul, mystery, and are enigmatic.

A great photograph needs both strong composition and content. You need a strong composition to add balance, harmony, and energy to an image. And you need interesting subject-matter (content) to captivate the viewer— and to make them see something they won’t forget.

When I am editing my shots (choosing my best images), I often ask myself: “Will people remember this photograph, or will it be meaningful 200 years from now?”

By thinking if a photograph will be memorable— it is a good way to filter through your “so-so” or “maybe” photographs.

Make photographs that will last at least 2-lifetimes. You can do this through strong compositions and strong emotions in your photos.

Articles on composition:

- Composition Lesson #1: Triangles

- Composition Lesson #2: Figure-to-ground

- Composition Lesson #3: Diagonals

- Composition Lesson #4: Leading Lines

- Composition Lesson #5: Depth

- Composition Lesson #6: Framing

- Composition Lesson #7: Perspective

- Composition Lesson #8: Curves

- Composition Lesson #9: Self-Portraits

- Composition Lesson #10: Urban Landscapes

- Composition Lesson #11: “Spot the not”

- Composition Lesson #12: Color Theory

- Composition Lesson #13: Multiple-Subjects

- Composition Lesson #14: Square Format

4. Photograph for yourself

What drives Koudelka to photograph? He is mostly lead by shooting just for himself. He explains below:

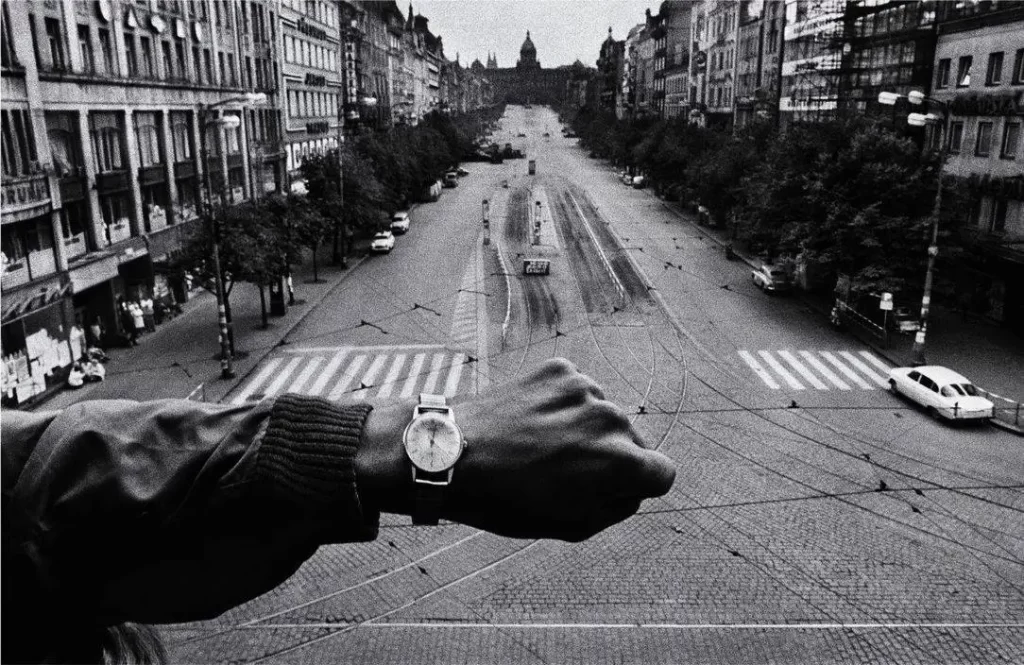

LH: Tell us about photographing the Soviet-led invasion of Prague.

Koudelka: I’d just gotten back from Romania, where for months I was photographing Gypsies, and my friend called me and said, “The Russians are here.” I picked up the camera, went out on the street, and I photographed just for myself. I’d never photographed events before. These pictures weren’t meant to be published. Finally they were published one year later, which is interesting, because they weren’t news anymore.

When Prague got invaded (Koudelka is Czech) he simply went out and made photographs. He shot them with no intention to get the images published in the news. He shot them for himself, to document the experience of what was going around him. In-fact, when the photos got published— they were first published anonymously.

Takeaway point:

Often when it comes to photography, we want to please our audience. We make photos to share on social media— to get likes, favorites, comments, and to gain more followers.

But Koudelka was born in an era where social media didn’t exist. To have your photos be featured was to have them in magazines, newspapers, or books. The process was a lot slower.

Even when he shot the Soviet invasion of Prague, the images didn’t get published until a year later— where the news was no longer relevant.

Sometimes we feel like in such a rush to publish the photos we make. But what is the hurry? Take your time. Make your photos for yourself first, and then perhaps publish them later (it is always to take your time).

5. Remain interested in photography

One of the most inspirational things about Koudelka is his longevity as a photographer. He has been photographing and traveling for over 45 years. What keeps him inspired— and what keeps him going?

As mentioned in this interview, even Cartier-Bresson lost his passion to shoot after around 30 years of photography. What caused Cartier-Bresson to put down the camera (and retire to just drawing and painting), while Koudelka continued to photograph?

Koudelka shares his shift from 35mm to shooting panoramic:

AS: The exhibition includes several panoramas. What attracts you to this format?

Koudelka: I love landscape. But I was never happy photographing the landscape with a standard camera. In 1986 I was asked to participate in a government project in France. They invited me to the office and I saw a panoramic camera lying on the desk. I said, “Can I borrow this camera for one week?”

In this case, shooting with a panoramic camera opened up his vision — and allowed him to work in a creative way he was never able to with a standard 35mm camera. It helped him get to a new stage in his photography— and to remain interested in photography:

Koudelka: I ran around Paris; I had to photograph everything. I realized that with this camera I could do something I’d never done before. The panoramic camera helped me go to another stage in my career, in my work. It helped me to remain interested in photography, to be fascinated with photography.

Koudelka: I’m going to be seventy-seven. When I met Cartier-Bresson, he was sixty-two. I’m 15 years older than Cartier-Bresson was then. And at that time Cartier-Bresson was stopping his work with photography.

Koudelka also shares the importance of love and passion for pursuing what you do:

Koudelka: It’s not normal to feel that you have to do something, that you love to do something. If that’s happening you have to pay attention so you don’t lose it.

Takeaway point:

I often say “buy books, not gear” on this blog— and generally am against “GAS” (gear acquisition syndrome).

However I do believe there is a difference between buying new cameras for the sake of getting the newest and greatest— and the concept of using different camera systems to open yourself up creatively.

For example, the difference between shooting with a Micro 4/3rds, a DSLR, a Fujifilm x100 camera, and a digital Leica is quite similar. But there is a difference between shooting with a digital camera and a 35mm film camera. And there is a difference between shooting with a 35mm film camera and a medium-format camera. And there is a difference between shooting with a rangefinder, a large-format camera you mount on a tripod, a TLR, a Hasselblad, or a panoramic camera.

So I guess my ultimate point is this: it is good to experiment with different gear, cameras, and formats. But let this experimentation liberate you creatively— don’t let it become a stress or a burden in your life.

For example, I know a lot of photographers who keep buying new cameras, lenses, and camera systems— which only adds more stress and complication in their lives.

Find a balance between experimentation and consistency.

Related article: Keep Shooting or Die

6. Empathize with your subjects

The photographs of Koudelka (especially in his “Gypsies” series) are so full of soul, emotion, and empathy for his subjects.

Koudelka shares more of his empathy and love in his photos below:

AS: In an interview at the Art Institute of Chicago you said you’ve “never met a bad person.” I see much empathy and love in your photographs.

Koudelka: That’s up to you [laughs].

AS: Are people fundamentally good?

Koudelka: I’ve been traveling 45 years without stopping, so of course things have happened to me that weren’t right. But even “bad” people behave a certain way because you don’t give them the opportunity to behave well. When you start to communicate with somebody, things go a different way.

AS: Can you give an example?

Koudelka: Have a look at the Russian soldiers [in my photographs of the Soviet-led invasion of Prague]. Okay, they were invaders. But at the same time, they were guys like me. They were maybe five years younger. As much as it might sound strange, I didn’t feel any hatred toward them. I knew they didn’t want to be there. They behaved a certain way because their officers ordered them to. I become friendly with some of them. In a normal situation, I’d have invited these guys to have a drink with me.

Koudelka: I can’t say I met one bad person [while photographing] in Israel either. Once I was in East Jerusalem with a photographer friend who went with me. We were planning to eat sandwiches under the trees. Suddenly, soldiers ran over with guns. One of them hit and broke my camera. But when I looked in his face, he had the same fear as the Russian soldiers in ‘68. I’m sure if I’d had the opportunity to talk to this guy, he would never have done that.

LH: To be a wonderful photographer, you have to have empathy for the human condition.

Koudelka: We are all the same. And we are composed from the bad and the good.

Takeaway point:

I think to be a great street photographer, you need to be an empathetic people.

As street photographers, we are in the business of capturing the human condition and soul. We try to capture moments, and the thoughts, feelings, and emotions of others. Without a strong sense of empathy— how could we relate to our subjects?

I think empathy in street photography can be interpreted in many different ways. It could be photographing others how you would liked to be photographed. It could be asking for permission before taking a photograph (if you are unsure how people will respond). It could be smiling at your subjects after taking their photograph, thanking them, and offering to email them a copy of the photo (or better yet, giving them a print).

Ultimately we all have a different sense of ethics, morales, and right-and-wrong.

You want to follow your own heart. Do what feels right to you. Follow your gut, and listen to what your soul tells you.

7. Separate yourself from your photos

One of the great points that Koudelka has taught me is the importance of separating yourself from your photographs.

A lot of photographers become emotionally attached to their photos— like their photographs are their children. And if you know any parents, you know that to call a parent’s child ugly is a definite no-no (even if it is true). Even if a parent had an ugly baby, the baby would look beautiful in the parent’s eyes.

I often use a phrase “kill your babies” when it comes to editing (choosing your best work). I fall victim to this all the time— I have such a vivid memory of taking the photograph, that it confuses me whether the shot is any good or not.

Therefore I am always asking people to critique and criticize my photographs. I carry them on my phone and iPad, and ask people to tell me which of the shots are interesting to them— and which shots are weak. Generally the good shots rise to the top (like mixing oil and water).

Koudelka shares more of separating himself (his ego) and his photographs:

LH: May we ask you to comment on a few of your photographs?

Koudelka: I wouldn’t talk about the photographs. No, I try to separate myself completely from what I do. I try to step back to look at them as somebody who has nothing to do with them.

Koudelka: When I travel, I show my pictures to everybody—to see what they like, what they don’t like. A good photograph speaks to many different people for different sorts of reasons. And it depends what sort of lives these people have. What they’ve gone through. It happens very rarely that you see something you can’t forget. That is a good photograph.

Takeaway point:

When you ask for feedback and critique on your photos, don’t feel a need to defend your photographs.

During a lot of critique sessions I do in workshops (or when just meeting other photographers in-person)— a photographer will defend their photos by saying, “Oh I know the composition isn’t so good— but there was nothing else I could do, my back was against the wall!”

However there is one thing you can ultimately control as a photographer: whether to keep or ditch the shot. Of course you can’t go back and re-shoot the same scene, but you have ultimate control as an editor of your own work.

I recommend you to always carry your photos with you no matter where you go. Have your photos on your iPad, your phone, or as small 4×6 prints. Whenever you have the chance to meet other photographers, don’t show off your photos to just have people pat you on the back. Share your photos with them to get honest feedback and critique— to know which shots work, and which shots don’t.

So now when I ask people to look at my photos, I ask them: “Please be brutally honest with me. Help me kill my babies.” And when they give me feedback, I force myself to keep my mouth shut (instead of defending my shots). I let them speak their mind, take their opinion to heart (if I trust them and respect their feedback).

Serape yourself from your photos. Your photos aren’t you.

Related article: Please Tell Me My Photos Suck (And How I Can Improve)

Conclusion

I think there is a lot we can learn from the life and photography of Koudelka. We can learn that it is important to live a life true to yourself, to follow our intuition and photograph what interests us, and to empathize emotionally with our subjects.

Learn more about Josef Koudelka (and street photography)

Other articles on Josef Koudelka

If you want to learn more about Koudelka, read my other articles on him:

- 10 Lessons Josef Koudelka Has Taught Me About Street Photography

- 8 Rare Insights From an Interview with Josef Koudelka at Look3

Recommended Articles

Here are some articles I hand-picked for you guys, related to this article:

Recommended books by Koudelka

- “Exiles” (a newly re-printed book by Koudelka, get it while it is still in stock. It used to cost around $300 when sold-out, and now it costs only $44 dollars).

- “Gypsies” (his greatest body of work, in my opinion. You can read my review of the book here.

Learn from the Masters

If you want to learn more from the master street photographers, here is the full list:

- Alec Soth

- Alex Webb

- Anders Petersen

- Andre Kertesz

- Bruce Davidson

- Bruce Gilden

- Daido Moriyama

- David Alan Harvey

- David Hurn

- Diane Arbus

- Elliott Erwitt

- Eugene Atget

- Eugene Smith

- Garry Winogrand

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

- Jacob Aue Sobol

- Joel Meyerowitz

- Joel Sternfeld

- Josef Koudelka

- Lee Friedlander

- Magnum Contact Sheets

- Magnum Photographers

- Mark Cohen

- Martin Parr

- Robert Frank

- Saul Leiter

- Stephen Shore

- The History of Street Photography

- Tony Ray-Jones

- Trent Parke

- Walker Evans

- Weegee

- William Eggleston

- William Klein

- Zoe Strauss